- Travel offer - from the Braunschweig City Marketing GmbH

- Contact: Events - of the Technical Universtiy of Braunschweig

- Artist’s Choice - Filmreihe im Roten Saal, Schlossplatz 1

- Childrens program

- SUMMER DREAMS / SOMMERTRAÜME - Concert

- Reading - RAY OF LIGHT

- Lichtparcours Walk - with personalities from the region

- The City-finder - BEI PESS u. PUSE

- Summerfest PLUS / Sommerfest PLUS - of the Municipal School of Music

- Summer Nights - in Braunschweig Cathedral

- Poems for ‘The Portal’ - from Writers Ink

- Artist Talks - in cooperation with HBK Braunschweig

- Lights Off - Finissage

Offers

Travel offer

from the Braunschweig City Marketing GmbH

GUIDED TOURS

As diverse as the artworks of Lichtparcours 2016 are, so are possibilities of discovering them with Braunschweig City Marketing GmbH. Guided tours on the Oker River by boat or raft, or on land by foot, with Segway or bicycle, or in a vehicle for visitors with limited mobility, all offer diverse and exciting perspectives on the light installations. Specially trained tour guides for city culture elucidate all things relevant, interesting and engaging about the exhibit and the Lion City. p>

CONTACT AND BOOKING

All guided tours and trips can be booked for groups. For detailed information visit the tourist information website.

Additional information concerning guided tours and travel packages for Lichtparcours 2016 is also available at the tourist

information center - Kleine Burg 14.

Contact: Events

of the Technical Universtiy of Braunschweig

The architectural work Satellites / Satelliten, developed by Tomás Saraceno, Bernd Schulz and students of the Technical Universtiy of Braunschweig / TU Braunschweig, provides a platform for regular screenings, exhibitions, concerts, and readings.

Thurs. June 16, 8:00 pm., Technical University Campus / TU Campus

Alexander Dorenberg plays rock music of the 70s and 80s.

Thurs. July 14, 8:00 pm., Technical University Campus / TU Campus

Marcel Pollex, founder of the reading stage "Kopf und Kragen,” reads from his recent publications. After the events, we'll put on the music at Torhaus Nord / Tor House North.

Artist’s Choice

Filmreihe im Roten Saal, Schlossplatz 1

From June through August, Lichtparcours Braunschweig 2016 will be offering the accompanying film series "Artist's

Choice," presenting the favorite films of the participating artists in the Roten Saal at the

Castle.

Organizer: City of Braunschweig, Department of Culture and Science, Cultural Institute /

Stadt Braunschweig, Dezernat für Kultur und Wissenschaft, Kulturinstitut

Admission: 5.00 € / 4.00 €

(reduced)

Tel. Ticket reservation:. 0531 470-4848

THE CITY OF THE BLIND // Thilo Frank

Wed., 22. June 2016, 7:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

CDN/BR/J 2008, Director: Fernando Meirelles, 116 Min.,

Rated 12

Zu Gast: Thilo Frank

To kick off the film series Thilo Frank will talk about his installation "You and I, wandering on a snake's tail," and introduce us to his favorite movie..

ETERNITY AND A DAY // Alfredo Jaar

Wed., 29. June 2016, 6:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

I/GR/F 1998, Director: Theodoros Angelopoulos, 130

Min., Rated 12

WITH HEART AND HAND // Andreas Fischer

Wed., 29. June 2016, 9:15 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1 Braunschweig

NZ/USA 2005, Director:

Roger Donaldson, 128 Min., Rated 0

2001: A Space Odyssey // Danica Dakić

Wed., 6. July 2016, 6:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

GB, USA, 1968, Direcotr: Stanley Kubrick, 143 Min.,

Rated 12

The shining // Tobias Rehberger

Wed., 6. July 2016, 9:15 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1 Braunschweig

GB, USA 1980, Director:

Stanley Kubrick, 119 Min., Rated 16

SOLARIS // Björn Dahlem

Wed., 20. July 2016, 7:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

UdSSR 1972, Director: Andrei Tarkowski, 167 Min.,

Rated 12

RABBIT'S MOON + EAUX D'ARTIFICE // Kai Schiemenz

Wed., 20. July 2016, 10:20 pm. (free admission), Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

USA 1950, Director: Kenneth Anger, 7

Min. + USA 1953, Director: Kenneth Anger, 12 Min.

APOCALYPSE NOW // Michael Sailstorfer

Wed., 10. August 2016, 6:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1 Braunschweig

USA 1979, Director:

Francis Ford Coppola, 153 Min., Rated 12

THEY LIVE // Kevin Schmidt

Wed., 10. August 2016, 9:15 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1

USA 1988, Regie John Carpenter, 90

Min., FSK 18

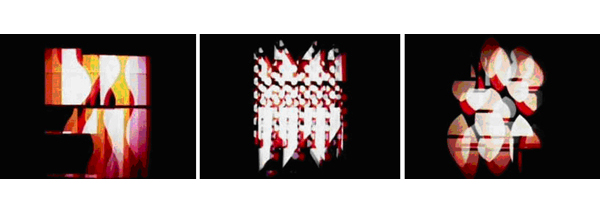

Reflective color-light show // Elín Hansdóttir

Wed., 17. August 2016, 7:30 pm., Roter Saal, Schlossplatz 1 Braunschweig

DE 1922-68, Kurt

Schwerdtfeger (Bauhaus Weimar), 18 Min., Experimentalfilm; Reflective color-light show , 5 Min.; Talking Backgrounds, 50

Min.

Childrens program

CITY LIGHTS

Tue. July 19, 2:00 pm.

Grandchildren and Grandparents Workshop, for children, age 6 - 12,

Kunstverein Braunschweig, Lessingplatz 12

From crates and boxes, we'll build the Braunschweig Palace, the White House, and self-designed pieces architecture, assemble them into a city and make it shine with a string of lights!

Material costs: 2,00 €

Organizer: Department of Culture and Science in cooperation with the Art Association Braunschweig / Dezernat für Kultur und Wissenschaft in Kooperation mit dem Kunstverein Braunschweig

Registration by email or telephone:

Tel .: 0531 470-4861

Email: lichtparcours@braunschweig.de

KIDS ART TOUR

Thursday: June 23, June 30, July 7, July 14, July 21, July 28 and more dates for groups on request (min. 10 participants) all dates at 8.00 pm., for children, age 6 - 13, with accompaniment

Meetingpoint: Steintorbrücke, Nordseite

At dusk, we'll be taking a look at the installations of Lichtparcours from a new side, and during a treasure hunt, enthusiastic riddle-solvers will learn the exciting stories of these fascinating artworks.

Admission: € 8.50 per child and adult escort

Organizer: Department of Culture and Science in cooperation with the Braunschweig City Marketing GmbH / Dezernat

für Kultur und Wissenschaft in Kooperation mit der Braunschweig Stadtmarketing GmbH

Registration by email or phone: Tourist Info Braunschweig / Touristinfo

Braunschweig

Tel .: 0531 470-2040

Email: touristinfo@braunschweig.de

LIGHT WORKSHOP

Tue. July 5, 11:00 am., Sat. August 20, 2:00 pm., child-parent workshop for children, age 4 - 10, Kunstverein Braunschweig, Lessingplatz 12

Whether street lighting, living room lamps or sunlight - without light, the world would be a darker place. Workshop participants will explore questions dealing with the subject of light before making an individual candle or tealight.

Material costs: 2,00 €

Organizer: Department of Culture and Science in cooperation with the Art Association Braunschweig / Dezernat

für Kultur und Wissenschaft in Kooperation mit dem Kunstverein Braunschweig

Registration by email or telephone:

Tel .: 0531 470-4861

Email: lichtparcours@braunschweig.de

LIGHT RESEARCHERS

Tue. July 5, 11:00 am., Sat. August 20, 2:00 pm., child-parent workshop for children, age 4 - 10, Meetingpoint: Bürgerpark, Drachenbrücke

What

is light and how does the human eye see it? Using Danica Dakić's installation as an example, we will investigate light in

detail and break it down into its components. With this newly acquired knowledge, participants will create their own

light-world in a plastic

bottle.

Material costs: 2,00 €

Organizer: Department of Culture and Science in cooperation with the Kunstverein Braunschweig / Dezernat

für Kultur und Wissenschaft in Kooperation mit dem Kunstverein Braunschweig

Registration by email or telephone:

Tel .: 0531 470-4861

Email: lichtparcours@braunschweig.de

SHADOW THEATRE

Tue July 12, 11:00 am., for children, age 8 - 14, Kunstverein Braunschweig, Lessingplatz 12

"Where there's light, there's shadow." Using the various artworks of Lichtparcours 2016, we will create large, small or even colorful shadows and silhouettes and think out short stories and scenes to go along with them.

Material costs: 2,00 €

Organizer: Department of Culture and Science in cooperation with the Art Association Braunschweig /Dezernat

für Kultur und Wissenschaft in Kooperation mit dem Kunstverein Braunschweig

Registration by email or telephone:

Tel .: 0531 470-4861

Email: lichtparcours@braunschweig.de

SUMMER DREAMS / SOMMERTRAÜME

Concert

Fri. August 5, 8:00 pm., Gartenhaus Haeckel / Garden House Haeckel, Theaterwall 19

Works by JS Bach, Mendelssohn, and Spohr. Set against the backdrop of Kevin Schmidt's installation, sounds and lights synthesize into an audio-visual experience. Vlady Bystrov, composer, and saxophonist will coordinate music and drama and present one of his works.

Admission is free.

Reading

RAY OF LIGHT

Sat. Aug. 6, 9:00 pm., On the hill of the former Ulrich-Bulwark, Museum Park / Anhöhe ehem. Ulrich- Bollwerk, Museumpark

Light as a topos in the history of literature: The Raabe-Haus / Raven House: Literature Center, embarks on a treasure hunt and arranges quotes from world literature into a text-collage. Kai Schiemenz' sculpture Bastion Beauté is the scene of the reading with contributions from Dorothee Bärmann, Jürgen Beck-Rebholz, Kathrin Reinhardt and Ronald Schober.

Admission is free.

Lichtparcours Walk

with personalities from the region

Braunschweig citizens and their Lichtparcours - walks to selected installations

Fri. June 24, 2016, 9:00 pm

Tobias Henkel, Director of the Braunschweig Cultural Heritage Foundation / Direktor der Stiftung Braunschweigischer Kulturbesitz

KAI SCHIEMENZ: BASTION BEAUTÉ

Meeting place: Haus der Braunschweigischen Stiftungen / Löwenwall 16

Fri. July 1, 2016, 9:00 pm.

Anke Kaphammel, chairperson of the Committee on Culture and Science / Vorsitzende des Ausschusses für Kultur und Wissenschaft

ALFREDO

JAAR: CULTURE = CAPITAL

Meeting place: Burgplatz / Braunschweiger Löwe / Braunschweig Lion

Thurs. July 28, 2016, 9:00 pm.

Dr. Gabriele Heinen-Kljajic, Lower Saxony Minister for Science and Culture / Niedersächsische Ministerin für Wissenschaft und Kultur

KEVIN SCHMIDT: ... BUT NO ONE'S HOME

Meeting place: Schlossplatz / Entrance to Castle Museum

Fri. August 12, 2016, 9:00 pm.

Gerhard Glogowski, Minister President of Lower Saxony (retired). and honorary citizen, CEO of the Braunschweig Foundation / Ministerpräsident des Landes Niedersachsen a. D. und Ehrenbürger, Vorstandsvorsitzender der Braunschweigischen Stiftung

DANICA DAKIC: FLASHBACK

Meeting place: Bürgerpark / Steigenberger Parkhotel

Fri. 19 August 2016, 9:00 pm.

Ulrich Markurth, The Lord Mayor of Braunschweig / Oberbürgermeister der Stadt Braunschweig

BJÖRN DAHLEM: M-SPHERES / SEYFERT 2

Meeting place: Bürgerpark / Steigenberger Parkhotel

Fri. 26 August 2016, 9:00 pm.

Prof. Dr. Susanne Robra-Bissantz, Vice President of the Technical University of Braunschweig / Vizepräsidentin der Technischen Universität Braunschweig

STUDENTS OF TU BRAUNSCHWEIG / IAC led by BERND SCHULZ and TOMÁS SARACENO: SATELLITE

Meeting place: Haus der Wissenschaft/ House of Science / Pockelsstraße 11

Fri. September 2, 2016, 9:00 pm.

Joachim Klement, General Director of the State Theater Braunschweig / Generalintendant des Staatstheaters Braunschweig

MICHAEL

SAILSTORFER: SOLAR CAT

Meeting place: John-F.-Kennedy-Platz / John F. Kennedy Square / Augusttorbrücke /

Augusttor-Bridge

Thurs. September 8, 2016, 9:00 pm.

Cornelia Götz, Dome Minister of the Braunschweig Cathedral / Dompredigerin Braunschweiger Dom

THILO

FRANK: YOU AND I, WANDERING ON THE SNAKE'S TAIL

Meeting place: corner of Petritorwall / Am Neuen

Petritore

Organizer: City of Braunschweig, Department of Culture and Science, Cultural Institute Stadt Braunschweig / Dezernat für Kultur und Wissenschaft, Kulturinstitut

Participation: free

Registration required: Tel.: 0531 470-4844 or by Email: lichtparcours@braunschweig.de

The City-finder

BEI PESS u. PUSE

Consistently during the complete run of Lichtparcours 2016, Tobias Rehberger's Art Takeout / Kunstimbiss, BEI PESS u. Puse will be culinarily and culturally recorded.

25. Juni

9. Juli

23. Juli

6. August

20. August

3. September

17. September

Summerfest PLUS / Sommerfest PLUS

of the Municipal School of Music

Sat August 20, 4:00 pm., Augusttorwall 5

A "children's music-playing parcourse," and a varied musical program of the Municipal School of Music / Städischen Musikschule will kick-off the evenings of the Summerfest. Performances by the Youth Symphony Orchestra / Jugend-Sinfonie-Orchestra, the Bigband and other well-known regional ensembles from the Music School provide a rich musical parallel to the Lichtparcours. Culinary delights will be provided.

Admission is free.

More informations: http://www.musikschule.braunschweig.de/

Summer Nights

in Braunschweig Cathedral

Sommernächte im Braunschweiger Dom

Sat. July 16, Fri. July 29, Fri. Aug. 5, respectively at 10:00 pm.

During Lichtparcours, Braunschweig Cathedral will also present itself in another light and immerse itself in color. The Cathedral also warmly welcomes visitors on three evenings, before or after the "Illuminated Walk through Braunschweig".

Admission is free.

Poems for ‘The Portal’

from Writers Ink

The inspiration for these poems was a visit to see the Lichtparcours Installation ‘The Portal’ at Braunschweig Harbour.

Like the artists who created the installation, the poets were intrigued and inspired by the harbour itself. It was like the discovery of a treasure-trove of history, travel and romance right at the edge of the city.

The poets belong to Writers Ink, and most write in English as a second language.

If you’d like more information about Writers Ink please contact rebecca.bilkau@icloud.com

Below are four Poems: The Granary by Angie Slotta, Brunswick Harbour by Ottmar Bauer, The Granary’s Voice by Stepahnie Lammers and Water’s City by Rebecca Bilkau.

The Granary

From a gritty patch of salty-sweet sand a galaxy of granulated stones is seen:

stretching

out to left, and right, and up, up, up;

one grain on top of another, densely

packed together - millions of concrete crystals:

structure walls, rooms, stores, until all of

it defines

the granary.

With a pulse in a rush: open the floodgates to the

arteries, send a tidal wave through its gut,

carry me on a sea of seeds: gravity pumps

nurturing nutrients

through the chambers of that big heart of cities: the supplier, the

origin

of industry is

the granary.

Unveiled by light: a changeling, a swarm of fireflies, a reflection of the stirring life inside;

outside on the crumbling building’s flank - board a barge tonight,

cut through the starry

waters on this journey through the past, echoing through the

night, illuminated before your

eyes, visible from a gritty patch of

salty-sweet sand next to

the granary.

Angie Slotta.

Brunswick Harbour (2016)

Future-eating one-man bunkers.

Yes, the two of you, standing there, unsmiling,

At the bottom end of the old

Brunswick dock,

Twinning for eternity. Round and streamlined

Like bombs dropped out of Hell, but

Square

eyed, square mouthed,

Ridiculously hooded and altogether dead,

Dead except for your insatiability.

How

do you do it, with jaws and maws

Cast in concrete, devour, chew, digest

All that moves forward, ships, dockers,

forklifts,

And, for starters, those innocent rabbits

That hop and mate and nibble

Across the weeded ramps

and lanes. Where

Are the hands, that more than patent metaphor,

Of what was once the harbour clock?

Gone

down your ghastly throats, annihilated.

Clever, clever, and in your limited perception,

Un-eared, dead-eyed, as

you are, not inefficient, either.

But there is a harbour outside – or so I hope –

Your range of greed,

ringing with the thuds

Of world-travelling containers lifted onto trains,

A harbour bustling with commerce and

internationality,

With barges, barely inches above the waterline,

That love to shove up mile-long billows

Along

the Mittelland canal, before they rest the night,

But never turn to set these rusty cranes to work.

The scrap

heaps, yes, I’ve seen them

And do not hesitate to call them goods;

They’ve taken root along the quay, and having

long

Befriended you, our pair of one-man bunkers,

Feel safe, like funny installations at museums.

Speaking

of which, there is a band of artists coming,

Who know that the more run-down a place,

The better the

inspiration, curious people.

I tell you, when they see you – yes, you,

The bunkers, and I’m still talking to you

–

For the moment they’ll forget about that white façade

Of more or less the harbour’s only storehouse,

Containing,

I am sure, floors and floors of obsoleteness.

That wall, so proud from all the grey,

Is meant to serve as

screen

For some as yet unknown, elaborate light show.

(Because, artists these days cannot be bothered

With

stark blonde nudes in oil, or sculpturing

From granite heroic guys, wielding spade or assault rifle.)

So, as I

said, seeing you, the kids will stand there

Wondering, and before long they’ll peep and

Poke into your bellies,

and like good artists

Penetrate the rubble with their minds.

I hope they’ll find the entrance down,

Down

to the horrid intestines of history.

And, hopefully before you act,

They’ll race back to their van and get out

Armfuls of equipment: projectors,

Cable drums, computers, parabolic mirrors.

And before nightfall there’ll

be: the slide.

Which inserted, will, my dears, my

Future-eating one-man bunkers,

Disappear you, will

disappear you altogether

Beneath a field of roses.

And I will stand

And watch and see what happens.

Ottmar Bauer

Einmannbunker am Hafen:

The Granary's Voice

With nightfall comes reflection.

Once the builders, traders, lever-pushers are gone

and have taken their noises

with them,

we regain our voices:

The canal laps up whatever stars, leaves or raindrops he

can catch, then talks about becoming a river,

about

hopping out of bed, one day;

of boldly flowing, where no bulldozer has gone before.

Their shift done, the young gantry cranes flex their sinews

and I listen politely, as they whinge and creak,

but

during the day they shuffled and stacked

containers from Hong Kong like Mahjong pieces.

Redundant as I am, I no longer have cargo for the barges,

but they share their voices, anyway. Same old, same

old,

they gargle, diesel-drunk, and how they’d like to laze in the swell,

instead of hauling ore, scrap metal or

gravel.

But then they murmur of landscapes and locks,

of destinations and docks, and of kissing quays in distant waters.

And

I, earthbound, obsolete, no longer a feeder of cattle or people,

I fall silent.

I have no regrets. I could have been built a munitions factory, or worse,

could have burned in storms of fire. Built

in ’33, need I say more?

Even though I am empty now, hollow, forever hungry,

without purpose or hope, I shall not

complain, but

I’ll gladly tell you about the golden nuggets of wheat and barley

cascading from floor to floor, as though to measure

time,

and about the dry whisper of black rapeseed and grey rye in my care,

and my endeavours to keep insects, mice

and pigeons out.

I’ll tell you about the tickle of the men, how they milled around

to keep the bread-in-waiting cool and dry,

how

they filled it into sacks, always busy, part of the great flow.

Until the men left for metal silos. Until the pigeons

came.

And I, with too much emptiness inside, turned myself into shelter.

I used to think of them as enemies, as rapacious

gluttons,

but now their cooing keeps me company;

voices in their own right.

Stepahnie Lammers

Water's City

for Braunschweig Harbour

We dream in opposites. They inform us.

We, in the

flatlands, where the sea

is mainly a rumour, we have sails

flapping through

our yards;

in the fathomless centre of night

they are the white shadows frightened Lovers

mistake for ghosts, who canny matriarchs

touch, finger to canvas air, and shudder.

What

mother does not fear the lure of water?

Transgressive,

shapeless, it is the ninety percent

of every child that eddies to freedom. That is,

disobedience.

Risk. The unfixable. The unbidden

inheritance

prayer can't erase. Water. It sloshes

through

sons, daughters, rendering them unreliable,

dilute,

strange. Strains the banks of family.

Opposites. Opposites. Water for heathland.

Poverty

for wealth. We, Braunschweigers,

gentle, observant, earnest, land at every edge

of

our existence, we dream we also dwell

on the Baltic, in league with its league.

Landlocked Hansa. Yes. We stretch past

local streams and trade talk with the sea

we believe might be, sleep easy, lush with wealth.

The

parent, the priest, we bring water

into

the fold; tame it. Name it our own.

Save

our young by dunking them in it.

Sprinkle

them on feast days, like it or not.

Scrub

them in it for punishment, pleasure

and routine. We hear we aren't unique:

Oker,

Volga. Same. Same.

Lush. The river is bounty. Rushes to be cut, dried

woven into the thrones we stow in our guild houses,

our workplaces, at the head of our tables, the thatch

that crowns our homes. There are fish too, caught

by us at the market. Wherever there is Need

there is an exchange. Money for life.

Life for money. We traders supply the need

we didn't create. And we are the heart of town.

The

standers-back, the teachers, the philosophers,

bless

us, we listen to the cheap

speak of the river; we have learned its letters;

we

know it is getting wily. Up to new tricks.

How to hide even when the sun pays

court

to the merchants. How

to

catch fish. The river is silting up.

And with a heart and a half, we look the other way.

Blank the kid pinching the plum, the doomsters

who say the river's running out –

show ourselves

wise. Pay no heed to pepper,

nutmeg, the burble of spice that hot tongued tinkers

peddle to fickle bellies. Cut our losses.

Say the Hansa trade is solid as rocks,

while we pull our boats from the encroaching ooze.

The talk of the river was the talk of the town.

It was the tittle-tattle of rittle-rattle pebbles,

shallow

tales. It kept gossip afloat. When it foundered

there

was a mud of silence, which some

mistook

for obsequy. No one but the water Readers

saw

the end of freedom rippling in. But. Blame no-one.

Even

shallow waters cut up choppy.

It was the encroaching dullness, caught our attention.

What wasn't dimmer was distorted. Our wives

told us they had told us we were captives in halls

of mirrors, river in sky, sky in river, and every harvest

between them brighter in the reflections. The Hansa

sank

and half our autonomy was on their deck. Half

our pride.

Our buoyancy gone, our gates flew open.

The Dukes surged in. Banned shanties.

Everything

seeps, fills. A storm in the Harz

raises the Oker, and the traders' hopes bob. Sun,

dries,

sinks, and they fall low. But in the pale

night,

another tide rises. We, the philosophers

and

teachers, we the mathematicians and poets,

bless

us, we engage ourselves with small sluices,

the

channels of thought we did not know we could think.

Our buoyancy surged from us, but not our will to float.

Every silk we traded, every bolt of calico

could, without a ripple of permission, turn

sail in

our hands. The millers' grain cascaded

through their stones. Horses' breath became mist

on the water meadows. When the brooks flooded

we nodded to ourselves, generation after dry

generation. Kept swimming.

We have found analogies for our calling

and

the buildings built for it. A college,

we

may say, becomes a scholarly confluence,

or

the estuary where salt and sweet theories

meet and become inseparable. Before they diverge.

No.

We may say, in our certain uncertainties

a

college is not a culvert, my learned friends, but a canal.

Keep these streams: Wabe, Schunter, Time.

Imagine

the swirl of a thousand thousand

unsung contracts, mergers, the sump of grief

at the

recurrent shock of death; and between

the bubbles of trade left to us, the rise,

rise, rise of our extemporisation. Wars? Come

and go. Napoleon had no eye for business.

The Kaiser, neither. We watered the earth.

Water, formed, governed. Calculated.

If

twenty men take two minutes to drink

a

pipe of ale, you sir, at the back, how many

mud

pies can you make from a ditch as Long

as a theoretician’s list of options, and if the answer

is

more than seven slag heaps how many backs

will

buckle, how many break, before the canal fills?

And. Earth moved, we heard. Collected in pyramids

on the road north. Bedrock, top soil, what

isn't fluid? A ditch to fill with cargo,

on

vessels on a man made flow. At beer we were gods

or engineers, inventing springs, sources, channelling

the Hansa. Time was a sail braced, swinging forward,

back, the clean clack of calico the tock and tick.

We saw barge ropes in our sinews. Prepared to dock.

Here

are the beautiful things: the Tools

our

need to calculate created. The curve

of

the compass, the elegance of the ruler,

all

their variations. The laws of average

by

which a town expands to its new harbour,

given

the chance. Given the lack

of

the incalculable glamour of war.

Halved whales, those barges, when they came. High sea beasts

ripping the canal's silk surface with awful calm;

and the steel in their bellies, the new grain. We gulped it back

with a dash of propaganda. Told ourselves we walked

on water, in the right uniform. Believed the opposite

of what we thought. Till the city drowned in fire,

the sky spat sparks, boiling all reflections; and we

suspecting we'd earned this, learned to fear thirst.

Hunger

eats the guts of deduction. We, the historians,

the

mediators of time, we had soot in our eyes at dawn,

as

if we'd painted caves with the hunters all night.

As

if the firestorm itself was a hypothesis

we

could reason away. First light, we stole to the towpath

to

measure the bluing of brown water. It was banked

by

cardboard khaki, Marshall planned. Food. Food. Food.

Opposites, opposites, rabble and silence,

rubble

and concrete, rivers and canals.

We took to building in our sleep,

constructing new

visions, brick by white slab.

Water, wherever it ran, was a private pleasure,

a genetic tick, twitching the blood. The canal

silent, still, threading through bright as grain,

light as winter. Mistaken for mundane.

There is much to be said for seeing a dream,

though

we, the planners and navigators,

we,

the dredger drivers, and pilots of barges, prefer

the

jargon of projects, maintenance, itineraries.

Do

not believe that is our only dialect. This wide, grey, green tide-free

organised

water, is our calling, our habitat.

We

sing its plainchant.

Hush. The stevedores have gone home; the great

containers shift in the earth's turn, China

setting into Holland. Metal waste

percusses

for the swaying frogs.

The harbour is dark, that is lit by two moons, and two stars

and we would not say which reflects which.

Sniff. Our town in this air. The scent of new coal,

fresh flour. In the granary, something germinates.

Rebecca Bilkau 2016

Artist Talks

in cooperation with HBK Braunschweig

LECTURE ALFREDO JAAR

Fri. June 10, 5:00 pm., Aula HBK Braunschweig

Faithful to the creed "99% thought and 1% action," Alfredo Jaar, in his conceptual works, deals with politically reprehensible practices and hidden power structures. Based on his work Culture = Capital / Kultur = Kapital (2016), realized in Braunschweig, the two-time documenta participant will present excerpts from his current artistic practice.

Moderator: Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker.

Admission is free.

ROUND TABLE: LEGIBLE LIGHT CITY

Mon. June 13, 4:00 pm., Aula Braunschweig

Four male and female artists of Lichtparcours 2016 approach the question of space and perception from different perspectives. The topic of the panel is the readability / non-readability of space, its markers and the space-time interconnection of perception.

Head of the panel: Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker.

Admission is free.

Lights Off

Finissage

Thurs. September 22, 5:00 pm.

Join us in celebrating the conclusion of Lichtparcours 2016 with an evening of music. Enjoy the program at different sites along the shore of the Oker river / Okerufer. At the end of the night, the lights of the artworks will be extinguished.